Kurosawa’s samurai: Seven Samurai, Yojimbo and Sanjuro

text by Grigoris Miliaresis

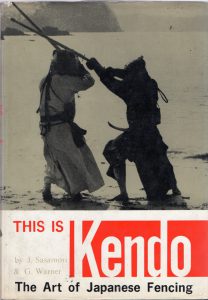

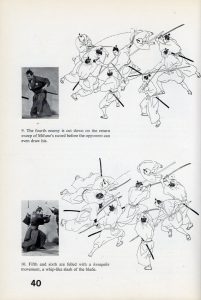

I don’t remember when I bought it (probably in the mid-80s) but I do remember how excited I was: my first book on kendo -which I’d never seen live. It was “This is Kendo, The Art of Japanese Fencing” and in its 160 pages, one Japanese teacher, Junzo Sasamori and one American, Gordon Warner were explaining what “Japanese fencing” was all about, I think for the first time in English. I could write a whole article about that book and perhaps one day I will but for now, I’d like to take you to its page 38. There and on the next three pages was an amazing set of illustrations depicting a fight between nine samurai: one against eight. The caption of the sequence read “Toshiro Mifune, Japan’s leading actor of international fame displays samurai virtuosity with his sword in a sequence from the film “Sanjuro””.

“This is Kendo, The Art of Japanese Fencing”

So here was a book about Japanese fencing, written by two renowned teachers which in its history and tradition section was illustrating real-sword samurai fighting using an actor! Incredible, even if he was “Japan’s leading actor of international fame” -weren’t any swordsmen available from the real classic schools that I’ve already read were still surviving? Those being pre-Internet days and in Greece (i.e. “Sanjuro” wasn’t available at my local video-rental place), I had to wait a few years for the answer. Which was that 1962 “Sanjuro” wasn’t just any film. It was created by one of the most important filmmakers in the art’s history not only in Japan but worldwide, Akira Kurosawa, and it was one of three black and white samurai-themed masterpieces of first period of his career –the other two being, of course, “Seven Samurai” (1954) and “Yojimbo” (1961).

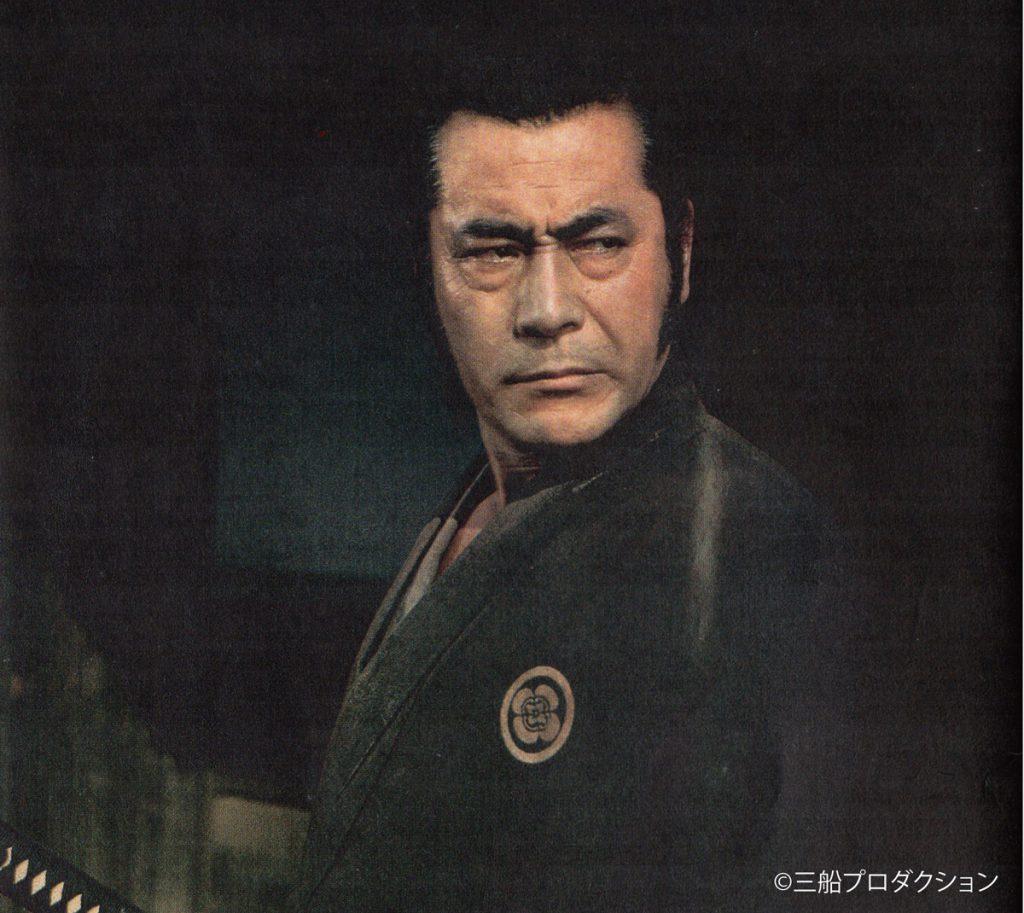

Flash forward to 2020: I am in Japan, I’m writing for a Japanese martial arts’ magazine and I’m practicing those old schools after having practiced enough kendo and iaido to be able to understand what Junzo Sasamori and Gordon Warner were writing about in that book that was published three years before I was born. Or rather I would be practicing if it wasn’t for the Covid-19 pandemic that has swept the whole world and, among other things, made us close our dojo and stay at home. Everybody has turned to their screens for something to help pass the time until the lock-down measures are lifted so perhaps this is the best time to re-evaluate those films –after all, this past month we had the double anniversary of 110 years from the birth of Akira Kurosawa and 100 years from the birth of the star of all three films, that Toshiro Mifune guy!

First Act: Seven Samurai

Seven Samurai (七人の侍 © 1954 Toho Co., Ltd.)

The story in a nutshell: During Sengoku Jidai, the time of civil strife, a poor farmers’ village gets raided by renegade bushi who have become bandits. To avoid their next invasion, which will happen after the rice harvest, the villagers hire six down on their luck ronin (masterless samurai) and an eccentric farmer-turned-samurai to defend them. The ronin manage to win the battle but not without severe casualties.

From a martial arts’ point of view –and I’ll be sticking to this in this article because I’m no film critic!- “Seven Samurai” is amazing. It contains swordsmanship, especially in the character of master swordsman Kyuzo who is selected by the villagers because he wins in a duel, spear fighting with actual yari and bamboo spears (the ronin teach farmers how to use them), archery, utilized by two of the samurai, among them by their leader, Kambei, matchlock gunnery (the bandits have three guns and at some point the samurai manage to seize two of them), horsemanship (the bandits are riders), and strategy, fortification techniques and tactics, all by the mastermind of the seven, Kambei. I haven’t been in a Sengoku Jidai setting but as a martial arts practitioner, I believe this is one of the most realistic depictions of such a situation.

Shooting of Kyuzo’s duel (Photo ©Yuishinkan Sugino Dojo)

Kyuzo’s duel when we (and the villagers) first meet him is one of the best swordsmanship scenes in cinema: first he duels with a bokuto but his opponent doesn’t accept he lost, claims it was a mutual destruction hit (ai-uchi) and presses for a redo with real swords. Unperturbed, Kyuzo takes his sword, the scene is repeated and the opponent gets cut down in one forward move –no sword clashing, no jumping around and no fancy moves. And how it could be otherwise when the sword choreography was done by non other than Yoshio Sugino, licensed teacher of Tenshin Shoden Katori Sinto-ryu and aikido student under the art’s founder Morihei Ueshiba? This isn’t stage fighting but as close as it gets to the real thing, taught by a real sword master!

Sugino Yoshio (1904-1998, Photo ©Yuishinkan Sugino Dojo)

But realism doesn’t stop there: the test the ronin leader performs to test possible recruits (he has another one waiting inside the house ready to hit anyone coming in with a bokuto) is a classic go no sen/sen-sen no sen scenario that could be taken by any classic ryu’s playbook; as a matter of fact, this is how, according to Ono-ha Itto-ryu records, Iemitsu Tokugawa tested Tadaaki Ono and Munenori Yagyu. The first samurai reacts to the attack, gets offended and leaves but the second doesn’t even enter and just laughs at the leader –the leader laughs back, asks him to join and he becomes one of the seven. And when the ronin get to the village, their whole deportment, their awareness and their understanding of what needs to be done before being told to, even though most of them have just met, shows the results of severe training and experience in conflicts, on and off the battlefield. The big fighting scenes are fine but the best budo bits of this 3,5-hour epic are in the details!

As a matter of fact, what I find less appealing both as a martial arts’ practitioner and as a viewer is Toshiro Mifune’s character, Kikuchiyo: he is the film’s comic relief but also the voice of conscience of the ronin when he delivers a monologue accusing the samurai class for making the lives of farmers miserable. But he is too physical and too farcical and from a 21st century perspective a little too much. Which makes the next film, “Yojimbo” a real surprise, because it’s a Mifune tour-de-force!

Second act: Yojimbo

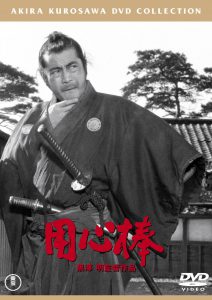

Yojimbo (用心棒 © 1961 Toho Co., Ltd.)

The story in a nutshell: In the late Edo Period, a ronin gets to a countryside town torn from the fight between two clans/gangs. His sword skills and presence make him look like an attractive ally to both groups that attempt to hire him as a yojimbo (bodyguard) but he manages to play both of them and make them destroy each other.

Mifune takes the lead in this film but his character is the complete opposite of his “Seven Samurai” Kikuchiyo –actually he’s closer to the “Seven’s” sword fighter Kyuzo. Sanjuro, the name of the character here, is also a master swordsman ronin who will draw his sword only when he can’t do otherwise. Most of the time he wins “saya-no-uchi” i.e. without actually using his sword but with being aware of the action, both seen and unseen (he understands people’s thoughts, motives and agendas) and knowing how to use it in the most profitable way. He is the perfect realization of the idea that swordsmanship is also strategy and the principle of preservation of one’s fighting resources until absolutely needed.

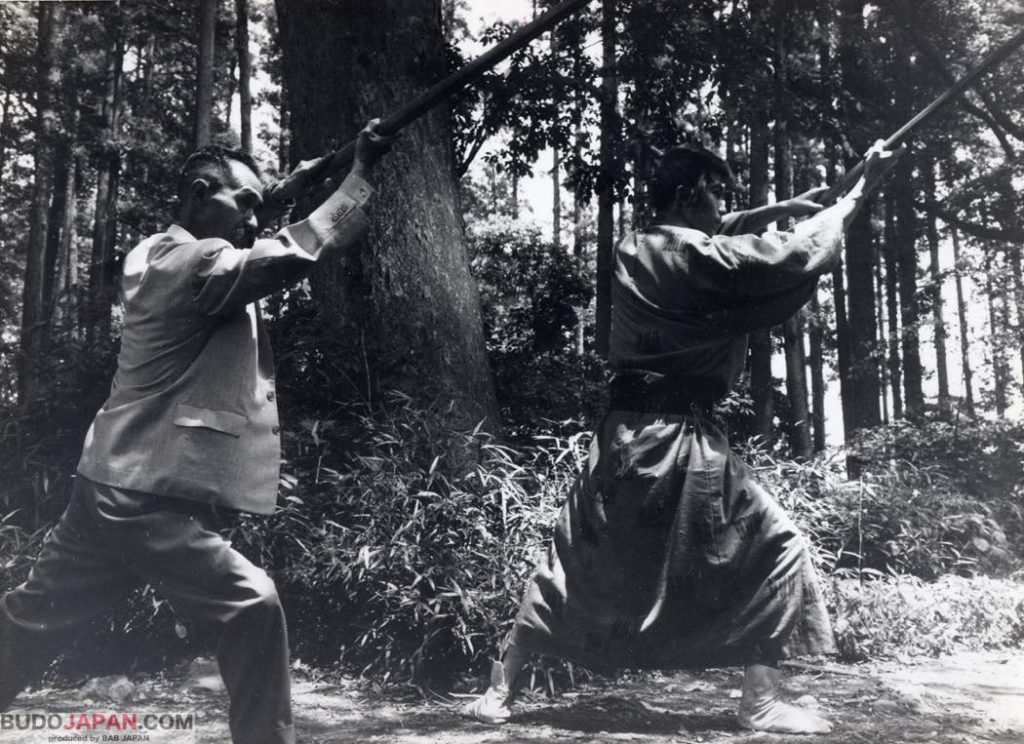

Yoshio Sugino teaching Katori Shinto-ryu’s “Gyakunuki-no-Tachi”to Toshiro Mifune. (Photo ©Yuishinkan Sugino Dojo)

But when he does take his sword out, his movement is masterful. Again guided by Yoshio Sugino, Mifune doesn’t waste time clashing swords or flailing his hands around like the gangsters do. Each cut is powerful enough to take an opponent out (and when it isn’t, the second is -which makes even more sense from a real sword fight standpoint) but can also be light enough to slice through an opponent’s clothes or a comrade’s restraining ropes without even touching the skin and he moves with speed and efficiency like an aikido master doing a multi-opponent randori, utilizing the terrain, available objects and mostly, the opponents’ bodies. And when the time comes to stay low and regain his powers, he practices with the only available weapon, a kitchen knife which he uses as a shuriken on leaves fluttering in the wind –as luck (and script) would have it, this proves useful when the time comes to face the gangsters’ main warrior who is carrying a Western revolver. Cool-headed, laconic, realistic to the point of cynicism, skillful in the arts of war, those fought with weapons and those fought with wits, Mifune’s Sanjuro is the ultimate samurai. And one year later, he returns with what could very well have been called. “Yojimbo v2.0”: “Sanjuro”.

Third act: Sanjuro

Sanjuro (椿三十郎 © 1962 Toho Co., Ltd.)

The story in a nutshell: Sanjuro, the character from “Yojimbo” meets a group of young samurai who have become pawns in a power game between their leader and another han (fiefdom) official. Reluctantly, he becomes their leader and helps them restore their leader and punish the corrupt official and his men.

If seen right after “Yojimbo”, Mifune’s character in “Sanjuro” has grown –now it isn’t just strategy that makes him use his wits instead of his sword but also the realization that not everything in life can be solved with a drawn sword. (The samurai leader’s wife mentions that and in the end he accepts that she was right.) Like in “Yojimbo” his power lies in having a good understanding of the terrain, the players and the allegiances and he uses the fascination of others with him and his skills to make things move in the way that best serves his purpose. And like in “Yojimbo”, his actual motive isn’t greed for money or power: he does want to fight evil but he’s too proud (and, let’s face it, cool!) to admit it.

Ryuu Kuze and Toshiro Mifune during the shooting of “Zoku Miyamoto Musashi” (Photo ©Yuishinkan Sugino Dojo)

This time sword work comes from Ryuu Kuze, who worked with Yoshio Sugino in “Yojimbo” so there are no seams: from Sanjuro’s trademark shrug when walking around (something that every kendoka will acknowledge comes from too much sword practice) to his kiri-age and ichimonji giri (rising and horizontal cuts, respectively) to his tai sabaki especially in the midst of many opponents (remember page 38 from the “This is Kendo” book?) everything is there, masterfully choreographed and executed. And when the time comes for the final duel with the bad guys’ head swordsman, Hanbei, it’s just one move-one cut, again like Kyuzo’s duel in “Seven Samurai”. As for the cartoonish blood explosion ending the duel, it might have been so the nine young samurai will realize the path of the sword was bloody but it became a standard for every bad samurai movie for the next 20 years!

Last act: Kurosawa’s samurai

Perhaps “Yojimbo” and “Sanjuro” aren’t masterpieces –“Seven Samurai” certainly is and cinema history has been pretty straightforward on that. But they aren’t simple swashbuckling chambara either and there is a thin line of realism running through all these films although it’s easier to see in the “Seven” and less in the other two. With these films, Kurosawa made people see the ronin under a different light (until then, they were basically the villains) and understand that they could have a personal code of ethics that sometimes could be more solid than that of the samurai serving under a lord. And for someone practicing martial arts, and especially sword arts, they draw a picture that even though would be overshadowed by the next 50 years’ endless acrobatic choreographies, is probably much closer to the reality our ancestors in the classic ryu lived in.

Yoshio Sugino teaching Toshiro Mifune “Kiriage”(Photo ©Yuishinkan Sugino Dojo)

The relaxed style of the main characters (and especially Sanjuro) and their instant explosion when there’s real action, like cats who go from nap to hunt in a fraction of a second, their awareness of the situations unfolding around them and their ability to lay down plans and adjust them according to changing circumstances, their calm demeanor against difficulties, even when these become life and death issues, are all excellent depictions of the qualities found at the core of almost all traditions and which all martial artists strive for. Add some great, and for the most part realistic, swordsmanship created by one of the 20th century’s most renowned classic martial arts’ teachers and some messages that could go as deep as anyone would like to –from deep philosophy about the nature of conflict to just everyday ethics as parameters of living one’s life, as true in the Edo Period as they are today (black and white they might be but there are countless shades of gray in them!) and you have something that anyone interested in the martial arts should watch at least once –or five times. Oh, and they’re damn fine cinema too!

Yoshio Sugino teaching Katori Shinto-ryu’s “In-no-Kamae” to film actors. (Photo ©Yuishinkan Sugino Dojo)

PS

Remember that illustration in the kendo book? I’ve watched “Sanjuro” over half a dozen times and still haven’t managed to locate it. Go figure…

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Toda-ha Buko-ryu under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis