Biography of André Nocquet Part 3: André Nocquet’s private diary

In the April 2020 issue of Hiden, I wrote about the life of André Nocquet, who was the first foreign uchi deshi of Ueshiba Morihei from June 1955 to October 1957. Nocquet passed away in 1999 and he entrusted his close student, Mr Frank Decraen as the caretaker of his belongings. Shortly before his own passing, Decraen designated me as his successor and asked me to find out as much information as I could from those items. I accepted his request and started to study them very carefully. Last month, I discuss my findings on a mysterious keikogi that O Sensei supposedly gave to Nocquet. Today, I would like to describe some selected parts of a private diary that Nocquet wrote during his stay in Japan, so that you can discover some of Nocquet’s inner thoughts, aspirations, and as for all humans, some of his intrinsic contradictions.

Before going further, I need to clarify that it is a very easy and foolish thing to do to criticize the misguided views of pioneers when one has the benefit from hindsight. In this article, I am not trying to undermine André Nocquet’s work nor personality, but on the contrary, I would like to respectfully shed some more light on his thought process based on my own meager Aikido experience and decade spent living and training in Japan. It is a worthwhile exercise as more than a window into a pioneer’s heart, this diary holds some of the keys that explain how Aikido is understood in the West today.

The first entry in the diary is dated August, 28th, 1956 and the last is from November 3rd, 1957. Even though the end corresponds to Nocquet’s departure from Japan, the entire period between his arrival and July 1956 is missing, which suggests that there either exists an earlier volume, or that Nocquet only started writing halfway through his stay in Japan. Either way, we are unfortunately missing the entire first year of his stay.

Aikido and Religion

Cover of André Nocquet’s private diary

The first thing that struck me when I received the notebook was the large black cross on its cover. Interestingly, many of the Japanese people to whom I showed it thought that this cross represented the bridge between heaven and earth that O Sensei used to talk about. Indeed, O Sensei used to call aikido “十字道”, the Way of the Cross, and he would also use an alternative way of writing it such as: “合気十”, the “Aiki Cross” [Note: For more information on those concepts, I encourage the reading of this article.] . It is of course very possible that Nocquet was told about this by O Sensei, but there is no reference to this particular symbolism in the rest of the document, nor in any of the writings of Nocquet that I have in my possession. For a westerner however, this cross has an obvious Christian meaning. Nocquet was indeed for his whole life a very devout Catholic, and those who knew him agree that there is no tdoubt that this cross is a reference to it. In fact, numerous parts of the of his diary feature excerpts from the Christian bible, such as this one, which is written on its very cover:

“He who loves the Crucifix often guards himself with its sign”

Canon John Mirk (c. 1400)

For a French person, the presence of this large black cross on a notebook that supposedly contains all sorts of secrets about the Far East is both unexpected, and possibly also a source of some unease. In fact, my friend Odilon Regnard, who acted as my witness when I was made the custodian of Nocquet’s belongings, strongly argued against publishing openly pictures of that front cover, for he feared that it might be misunderstood. I think that even though it likely has very little to do with O Sensei’s use of the symbol, this cross is actually the key to Nocquet’s thinking and his understanding of Aikido, and possibly, that of a whole generation of non-Japanese practitioners.

Nocquet formally addressed the question of religion in Aikido in an interview that he gave on a French radio show in 1988:

One day I asked my master, Master Ueshiba, “You always say that Aikido is Love. Then, isn’t there a very tight link with Christianity? ” He told me, “Yes, there is a very tight link with Christianity, but when you return to Europe, never say that Aikido is a religion. If you practice Aikido well, you may become a better Christian, but if a good Buddhist practices Aikido, he will also become a better Buddhist. Aikido is a way, a path, it helps to better understand religions and philosophies, but it is not a religion.” This is what he told me.

Interview with André Nocquet – France Culture, 1988

Here it is clear that Nocquet took O Sensei’s answer as a sign that his Catholicism and the spiritual ideals of Aikido were not mutually exclusive. He went further later on though, arguing that Ueshiba Morihei was actually advocating a sort of syncretism between the world religions and the spiritual ideals of Aikido. As a result, in his own writings, Nocquet later often attempted to merge Christian concepts with Ueshiba’s ideals.

To reach this aiki, it is necessary to “build the divine soul in the human body”, that is to say, to associate with universal Ki, which is quite difficult, by the practice of shin-kokyu and then everyday life in God. “Let your light shine in the darkness around you”. If God – Christ is always present in us, we will live divinely, and our Ki will then be able to penetrate everywhere, “Through doors, walls, rocks, anything”; it is an enormous power to have Ki in oneself, it is quite natural then that the malicious attack is quickly thwarted and absorbed, annihilated, erased, destroyed. We must go forth without hesitation.

Entry from André Nocquet’s diary dated 27 September 1956, following a class with Ueshiba Morihei

In particular, Nocquet makes frequent parallels between breathing (shin kokyu) exercises and prayer.

Breathing. Prayer. Two important elements of aiki.

Entry from André Nocquet’s diary dated 17 April 1957, following a class with Tohei Koichi

Through his lectures and writings, it is evident that Nocquet seems to have taken this as a licence to adopt a largely ethnocentric point of view when analyzing and describing what the philosophical principles of Ueshiba Morihei’s art were. As an example, I have discussed elsewhere the differences in the concept of harmony between Japan (和) and the west, and the potential misunderstandings that may arise if one looks at harmony within the framework of Aikido based on an ethnocentric and/or contemporary interpretation of the term. Like many early practitioners, what Nocquet wrote was often based on such misunderstanding.

Nocquet praying with O Sensei.

One can actually argue that this may have led to some misinterpretations about Ueshiba’s art and intentions, since Nocquet did not have a particularly sophisticated understanding of Japanese mind, culture, or language. He was also a very experienced man when he arrived in Japan, very far from a blank slate. Therefore, he read everything through the prism of his own Western philosophy, and as we all are, was often prone to confirmation biases. For instance, Nocquet often omitted to highlight that the dogmatic nature of the claims that a religion like Roman Catholicism makes are mutually exclusive with that of other religions, even those, like Buddhism, which are not based on dogma and therefore more malleable.

Master Ueshiba explains the beginning of the world in the same way as the bible (without knowing it). There is a point at the beginning. It is Ki, that is to say, a universal spirit – God – the spirit of God. Then Ki manifests itself by a sound, the verb which has the power to create, which explains the rhythmic movements of the Master with accompanying sounds. It means that by emitting sounds the Master absorbs the beneficial (universal) cosmic energy.

Entry from Andre Nocquet’s diary dated September 27, 1956

A little further in his diary, Nocquet draws one of the numerous clear and direct parallels between scriptures and the practical interpretations of Aikido.

I read in the Bible today (Luke 8:39): “Jesus did not let him, but said, “Go home to your own people and tell them how much the Lord has done for you, and how he has had mercy on you.””

God acted in Jesus, it was total aiki; similarly, Jesus can act in us who are alive if we let ourselves be guided by him, our body being a simple instrument in the service of Jesus. It is not we who speak, act, it is Jesus who is in us who does everything, this is the real aiki.

“When you are brought before the synagogues, the magistrates and the authorities, do not worry about how you will defend yourself, or what you will say because the Holy Spirit will teach you right now what it will take say.” Luke 12:11

When you are attacked by the opponent in real combat, do not worry about how you will defend yourself, or the technique you want, because Ki = Holy Spirit will teach you right now what to accomplish it.

Entry from Andre Nocquet’s diary dated November 3, 1957

The other side to this observation, which gives some more insight into Nocquet’s character and thought process and set of values, is that on a number of occasions, he made rather derogatory statements regarding scientists or the scientific method itself. He often resorted to the appeals to authority and cited as models scientists whose views have been largely disproved since, such as here:

As for Sir Fred Hoyle, Founder of the Cambridge Institute for Theoretical Astronomy, knighted by the Queen of England for his work, he rejects most of the theories on which our knowledge of the Cosmos is based. He sends Darwin, Einstein and Carl Sagan back to their studies.

André Nocquet – Maître Morihei Ueshiba Présence et Message p 250-251

As expected from such a statement, Nocquet’s writings often contain pseudo-scientific and new age concepts. One should therefore always keep those observations in mind when reading Nocquet’s words, for they can otherwise lead to gross misinterpretations about Aikido or Ueshiba Sensei’s intentions. I am afraid that those misinterpretations have permeated deeply through generations of practitioners, especially since for reasons I briefly explained in Hiden issue of April 2020, almost none of Nocquet’s own students ever went to Japan, nor studied Japanese culture, thought, or language.

Incidentally, since Nocquet mentions the famous scientist Carl Sagan, it is interesting to note that Sagan was also read and cited by none other than Nidai Doshu Ueshiba Kisshomaru. In his book “The Spirit of Aikido”, Nidai Doshu wrote the following:

“Cosmos” is not a philosophical treatise, but it contains a wealth of information on the most recent data in space science. And it does remind us once again that the universe is the source of our life and that our lives are intimately connected with its order and change. On this very point, although from entirely different perspectives, there is agreement with the intuitive understanding of life in East Asian thought.

Ueshiba Kisshomaru – The Spirit of Aikido p. 28

The contrast in approach is quite fascinating.

Daily practice and study

The entries in the notebook offer very valuable information about the practice and day-to-day life of Nocquet during that period. The notebook is indeed, to a large extent, as much of a technical memorandum as it is a diary.

Technical sketches made by Nocquet in his notes

Before delving into specific passages, it is important to note one last sentence taken from its cover, which perhaps illustrates better than anything, the all too human, intrinsic contradictions of André Nocquet. Keep in mind that Nocquet has been one of the most prolific writers to ever write about Aikido.

Should one write about Aikido?

For centuries we have written about physical love. The greatest personalities would learn nothing from it, physical love must be executed to understand it, that is to say feeling in silence the union with the partner. The art also, must be practiced, the understanding of this art is intuitive, this is why the greatest founding masters have never written much. If you write in a notebook, it is the notebook which will remember, but not you.

From the cover André Nocquet’s diary

This may also explain why Nocquet might have started writing only halfway through his stay in Japan. Note however that regardless of his fluctuating opinion on the matter of writing, he was expected to produce a report upon his return to France, and I would find it very surprising if he had not kept a record, albeit a loose one, of his first twelve months in Japan. Unfortunately, I was unable to confirm if any other notes than the ones I received ever existed (annexes to the diary exist but they are mostly posterior to that period). It must however be noted that as prolific a writer as he was, Nocquet never published any technical manual per se. There are however films that were shot towards the end of his life and that were intended for the making of an instructional video, but it was never completed for reasons I don’t know.

Excerpt from an unfinished technical video by André Nocquet (uke : Bernard Boirie)

A native French speaker cannot but be struck by the deep feeling of isolation permeating from Nocquet’s journal. Though he does actually explicitly mention his isolation in a couple of sentences, it is in a later text that Nocquet expresses the full extent of his loneliness at the time:

My ignorance of the Japanese language has, for almost three years, locked me in near solitude. As painful as it was for me at times, it placed me in ideal conditions for meditation.

André Nocquet – The Strength of Japanese Spirit (published June 1983)

It seems that this isolation would only be broken in 1956 when Tohei Koichi returned to Japan after a year spent in the United States. Even though the philosopher Tsuda Itsuo sporadically attended meetings to translate O Sensei’s words for Nocquet, he was not with him on a daily basis, so Tohei would have been the only instructor at Hombu at the time with whom Nocquet would have been able to communicate in English. Interestingly, Tohei’s return date also coincides with the beginning of the diary.

André Nocquet with Tohei Koichi at the Hombu Dojo (photo kindly given to me by Kobayashi Yasuo Shihan)

If one assumes that the notes that Nocquet took were based on the materials that most connected with him, or that he understood best, it gives us a very interesting perspective on what his main influences were. Even though Nocquet attended most of the classes of Ueshiba Kisshomaru Sensei, Okumura Shigenobu Sensei, and Osawa Kisaburo Sensei, the overwhelming majority of entries in his journal report on the teachings of Tohei Sensei. Tohei was probably the one who made the most effort to adopt a Western-like pedagogical approach and he seemingly also took it upon himself to explain the techniques of O Sensei to Nocquet. Indeed, Nocquet reported that Tohei told him the following:

Master Ueshiba is a genius in what he does. He cannot explain to you. I can explain it to you.

Interview with André Nocquet – Aikido Magazine – February 1984

The diary also helps us understand that Nocquet did the majority of his training at the Hombu Dojo in Tokyo. Even though there is a relatively large collection of pictures that show him in Iwama with O Sensei, which has led some people to assume that he trained there extensively, they were all taken during a single, 5-day trip to Ibaraki. I asked the Aikikai Ibaraki Branch’s Isoyama Hiroshi Shihan about Nocquet, and he responded that Nocquet was indeed not a regular of the Iwama Dojo, even though he may have visited at times.

Ueshiba Morihei and André Nocquet in Iwama

This further reinforces the idea that like for most of his contemporaries, Nocquet’s learning was placed under the responsibility of then Hombu Dojo-cho, Ueshiba Kisshomaru, as well as that of the Shihan Bucho, Tohei Koichi.

Future plans for the spread of Aikido abroad

In his diary, Nocquet often reflects on the teaching and organisation of the Aikido that he learnt in Japan, when he would return to France. He seems especially preoccupied by the establishment of a pedagogic system in order to ensure that Aikido would not be lost or denatured during the transmission and expansion process.

One might respond that Aikido changes every day and is going to go through more changes. Nevertheless, with its current degree, which is close to perfection, it is possible to establish a system now so that the instructors can teach it, always in contact with the Aikido Headquarter, which will update them on the various modifications made to perfect the art. A newsletter can also be created to serve as a link for all teachers.

Entry from André Nocquet’s diary dated 28 August 1956

Incidentally, Nocquet’s assumption that Aikido will keep evolving under the guidance of the Aikikai is quite interesting, and at odds with the rather rigid conception that many Aikido practitioners, including Nocquet’s own students, have of the art.

It is unclear whether things were explicitly expressed in those terms in Japanese during the classes at Hombu, but throughout Nocquet’s journal, the applicability of techniques for self-defense is often at the forefront. He also constantly refers to the way he would apply what he learnt in Japan when he would teach police forces and the army once he would return to France. This is obviously in stark contrast with practice at the Hombu Dojo today.

Nocquet often opposes the self-defense based on aiki to that of Kawaishi Mikonosuke (founder of French Judo). Even more fascinating, Nocquet never mentions Kawaishi’s full name, referring to his method as “Judo method”, “Kawa method” or “K. method”, almost like a secret code. The psychoanalytically-inclined may read a great deal into this of course.

Returning to France, I will have to be armed with a knife and provoke some experts of normal self-defense; they will all defend themselves according to the blockages of the K. method but I will yield to these blockages according to the universal principle of nonresistance.

Entry from André Nocquet’s diary dated April 1st, 1957

André Nocquet taking ukemi for Kawaishi Mikonozuke. This demonstration performed during the first edition of the European Judo Championship that took place on the 5th and 6th of December 1951 at the Vélodrome d’Hiver in Paris in front of more than 10,000 spectators.

This is yet again another contradiction in Nocquet’s character, who throughout his notes and public writings, speaks of not competing, letting go of ego and confrontation, yet explicitly describes in his private journal his intention to accomplish what the Japanese reader might call dojo yaburi (dojo storming).

Those who knew him know that Nocquet was a proud man. One section of his journal gives an interesting illustration of this. It contains a transcript of a speech that he gave to a foreign audience on the occasion of a celebration of the end of the First World War. Some crossed out and edited sections appear within the text:

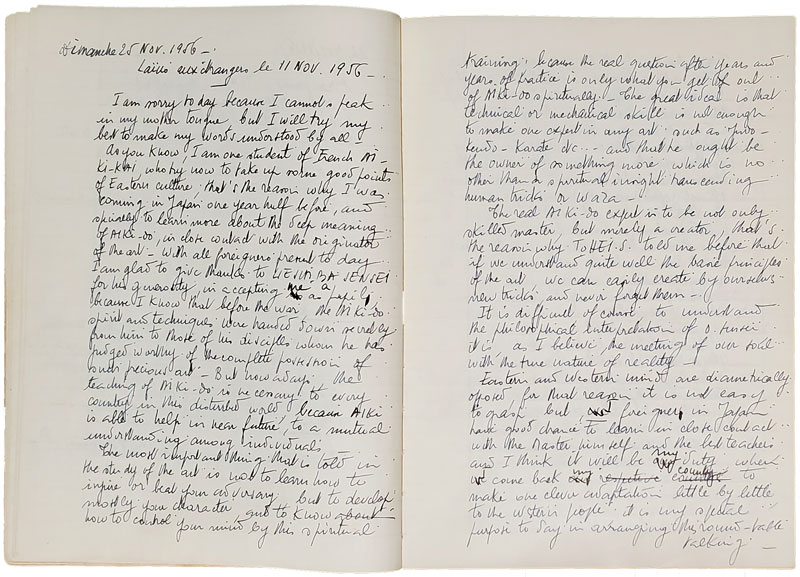

Speech to foreigners on November 11, 1956

[…]Eastern and Western minds are diametrically opposed, for that reason it is not easy to grasp, but we I foreigners in Japan have good chance to learn in close contact with the Master himself and the best teachers and I think it will be our my duty when we I come back in our respective countries my country to make one clever adaptation little by little, to the western people ; it is my special purpose today in arranging this round table talking.[…]

Entry from André Nocquet’s diary dated 25th November 1956

Given that the date of transcript is posterior to that of the speech itself (written in English in the diary), it is unclear why he would have transcribed the original version and crossed it out. Did he pronounce the original version a few days before and decided to modify a transcription meant for posterity? Who knows. It is undeniable however that Nocquet was not the only foreigner to train at the Hombu Dojo at the time, though he was the only one to live there. He wasn’t the first foreigner to be exposed to O Sensei’s Aikido either. Could this be seen as an attempt to direct the attention to himself? I guess we will never be able to tell for sure.

Transcript of Nocquet’s speech given during the November 11 celebrations in 1956. Note the passages that were scribbled using a different pen and that change the plural pronouns into the singular.

What we know however is that when he returned to Europe, Nocquet expected that he would become the head of Aikido on he continent. Unfortunately, this was not to be the case, partly due to his peculiar character, but also because of the refusal of some locals to accept his leadership, and to some extent, to the Aikikai’s decision to send other Japanese experts to take over this leadership. I won’t go into details but this caused a lot of issues, some of which had to be dealt with in front of the tribunals. It is one of the reasons why Aikido is as segmented as it is today in France. Kisshomaru Doshu writes a very interesting account of this:

A heart-to-heart communication that keeps on living

After extending his initial two-year stay to four, diligently devoting himself to the training of Aikido, Mr. Nocquet left Japan in 1959. Though I trusted his good faith, he did not always meet my expectations after he returned to France. Indeed, after Mr. Abe returned to Japan, the subtle differences in the way of thinking between the East and the West, the conflicts between the newly sent Japanese teacher, and the varying conflict of interest between French people resulted in him distancing himself from the Aikikai. However, I stayed calm and did not complain about it nor hate Nocquet for it. Aikido is about always caring for the other person and refusing conflict. I thought to myself: “When the time comes, they will eventually come to an understanding”.

A few years later, when the International Aikido Federation was established, I unexpectedly heard from Mr Nocquet that he wanted to visit Japan. Hearing this news after such a long time brought up familiar feelings to me, my wife and children. The warm heart-to-heart interactions that we had fostered between human beings was still alive, no matter what happened. After that, Mr. Nocquet settled his disputes with the local Japanese instructors and became closer to us once again as an organization.

Ueshiba Kisshomaru, Aikido Ichiro (p.229-230)

The path ahead

The study of Nocquet’s diary has been invaluable and extremely enlightening on many levels. It made me realize that just like Ueshiba Morihei, and by extension all humans, André Nocquet was full of contradictions. In fact, is Aikido also built upon those contradictions. Though our art proposes to avoid or resolve conflict, it holds at its very core the sources of discord that it offers to solve. Notably, it is a deadly art that aims at doing no harm. It is a revolutionary and flexible philosophy, yet it is culturally very anchored in Japanese mindset, all the while also being meant to be spread worldwide. No wonder then why there are so many different interpretations of Aikido, not only abroad, but also in Japan. This, however, is precisely what makes it worthwhile to dedicate one’s lifetime to the study of Aikido.

This study of Nocquet’s life and belongings also resonated on a very personal level. I wrote in the previous issue (June 2020) that I used to dream as a child to follow in the footsteps of my heroes André Nocquet and Christian Tissier, and come to study Aikido in Japan. I fulfilled that dream and over the past ten years, I have learned tremendously on the tatami of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. However, I also found out that it would be a mistake to cut myself off from those men. Indeed, the careful study of the pioneering journeys of my seniors through the reading of André Nocquet’s personal journal, or my private conversations with Christian Tissier, the analysis of their understanding and their characters, hold invaluable leads and lessons on my own path in Aikido.

To conclude this analysis, I would like to offer one last citation taken from Noquet’s journal, one to which I wish to adhere as I humbly follow in their footsteps:

Our path

I solemnly swear that for this one day, I’ll not get angry, nor feared, nor grieved.

I’ll be honest, kind and cheerful, fulfilling my duty to my own life with force, courage and eagerness, and living always as a respectable man with a mind of full peace and love.

Excerpt from André Nocquet’s diary dated 24th January 1957, following a visit at the Tempukai

Many thanks to Odilon Regnard for his help in the analysis the many documents from André Nocquet’s archives. Thanks also to Frank de Craene and Claude Duchesnes for their trust. This series of articles is dedicated to the memory of Frank, who asked of me only one thing: “The truth, nothing but the truth. “

About the author

Guillaume Erard

Guillaume Erard is an author and educator, permanent resident of Japan. He has been training for over ten years at the Aikikai Headquarters in Tokyo, where he received the 6th Dan from Aikido Doshu Moriteru Ueshiba. He studied with some of the world’s leading Aikido instructors, including several direct students of O Sensei, and has produced a number of well regarded video interviews with them. Guillaume now heads the Yokohama AikiDojo and he regularly travels back to Europe to give lectures and seminars. Guillaume also holds the title of 5th Dan in Daito-ryu aiki-jujutsu and serves as Deputy Secretary for International Affairs of the Shikoku Headquarters. He is passionate about science and education, and he holds a PhD in Molecular Biology. Guillaume’s work can be accessed through his website and on his YouTube channel.